Waitressing At Magoo’s © Jane Sherry March 2021

This is a story set in motion by a winter’s dream,

having nothing to do with Magoos. In the

dream, there was a mountain view at a party I

‘crashed’ where camellia blossoms fell on my head;

winter’s red flowers.

From that mountain-scape dream I found other

remembrances of the lands I’ve worked and lived

and loved; and to the singular jobs I’ve held- waitress,

bartender, topless dancer, personal assistant to a

celebrity drug dealer, wandering artist with

many more tales to tell.

The storybook of my grown up life begins so far from

the mountain view in that dream, so different from the

wild urban spectacle of my early twenties. This is one

of those stories.

Once upon a time I stole red tulips from New York’s City Hall.

I always was a flower thief.

I was young and in love with a city broke and dirty,

rent I could afford and flirting flirty; madly inspired

with my ponytail swinging I served up chili, burgers

and ratatouille, a waitress job to remember forever.

We were poor artists, soon-to-be-famous-artists, to

never-to-be-known-artists, forgotten artists. I served

their wives, their lovers and their children, to their

looks of dismay and approval.

It was NYC in the 1970’s, where there was an endless

party at Magoo’s, an artists-for-artists hangout on the

corner of 6th Avenue and Walker, down Tribeca way,

when rent was still cheap and love was easy,

booze, burgers and ratatouille; artists with bar tabs

and lots of promiscuity, and city hall rats made

backroom history at Magoos.

Pandy, the owner’s daughter, took me back there and

told me the story, it was like a fairy tale; in whispers

she made history re-membered; City Hall bigshots,

who paid for women in the back room; of everyday

corruption, and only later, did I hear of grand juries

and paltry fines

that finally closed that oasis of a gone-gone era

of cheap drinks and burgers for art; leaving artists

stranded, maybe missing that food and easy times

with their bar tab too, as the city kept changing.

Gentrification was creeping further downtown

and the artists diaspora-ed to the lower east side,

to Washington Heights, to Brooklyn and beyond;

to fame, infamy and oblivion.

Was it women of the Night? Call-girl or whore, I don’t

recall her exact words; the language she used for

the ladies of the night, in her story about city hall

big-shots, amidst the booze and ratatouille, the endless

soiree that was Magoos Restaurant in New York City

down Tribeca way.

What did she call them, I don’t remember; only that

her father, Tommy, (not Magoo), pimped women to

they-shall-remain-nameless, men from NY’s City Hall.

Tommy called them “high class prostitutes”, the

beginning of his fall.

It was more like a closet hidden off the dining room;

which housed storage for restaurant flotsam, for

those red lumpy candle holders too- ugly even then,

in that hidden-hidden room.

John Torreono gum-drop painting on the wall.

Bill Jensen was kind and soft spoken, even then.

There was Farb and Minter and Rifka, her not so

kind glances and others’ work I don’t recall,

traded for bar tabs and food.

Julian Schnabel, not yet art-crock-myth-maker

would drop in to Magoos for cheap coffee; he’d sip

it real slow, then little by little added milk from the

small pitcher that came with it. He’d sit there

and sit there and drink his milky coffee,

always alone until the pitcher was emptied.

That’s what I seem to remember. And then there was

Spencer, a kind-giant-of-a-man, a friendly ‘regular’, who

lived a block from Magoos, on the corner of Canal

and West Broadway; after my shift, we’d go for a quick

toke on a joint, then off to the clubs for me. All those artists,

all that art, who does it feed? Who has it now?

NYC streets were my art supply store. I found pieces of fabric

outside sweat shops and glittering debris from the streets.

From the dark and dusty scientific supply down on Chambers

street, like a museum really, I found crescent shaped early

20th century surgical needles which took pride of place by

test tubes, old spectacle lenses, glass slides and beakers,

tubes and petri dishes.

These I placed alongside the piles of red petals, stamens and

pistils stolen from the park at City Hall; peach pits and

glass slides, petals and papers from my gleanings

of the city streets. My Nature was gravity on that granite

island; the sense of place created by those two rivers,

named East and Hudson.

Those red and blue-black piles, of petals and pits, evidence

still, that there was a natural world in my beloved city,

as they sat on the shelves in the wood framed,

glass display case from a Brooklyn bakery that the

mother-of-my-Polish-boyfriend offered to me.

I always was a flower thief.

He brought it to the room I illegally rented, in the financial district

on John street, down from the dark Trinity Church, with a

bathroom down the hall and a shower stall six flights up,

the luxury of showering, a cost shared amongst the women

artists who lived there.

We played and performed at the beach on the-then-defunct

West Side Highway and on the plaza of those monoliths,

the buildings-in-progress later called The Twin Towers, which

forever became a kind of compass, a way to find south

in the city. Another kind of gravity.

My Polish boyfriend found his shimmering supplies as

he and his camera both watched the sky out the north

facing windows of the American Thread Building, across

from Magoos, capturing the changing light and shadow

frame by frame in his Stan-Brackhage-inspired movies,

making his New York beautiful in abstract yet figurative

portraits of the city that I loved, night into day.

I placed my venerable treasures to rest on those bakery shelves

where Poppy seed rolls and Chruściki (fried angel wings)

dusted with sugar once sat, now filled with bright red tulip petals,

dried blue-black stamens and pollen dusted pistils next to broken

glass, and a crushed up topaz gem from a pendant

my grandmother used to wear.

That was my garden – the jewels from the trash of the city in

my little studio, where I lived with two cats, one named Sapphire,

the other’s name I forget; and with artists and musicians and poets

all around. There were legal tenants, too, like the jewelers, whose

lost wax works I could smell at night, with offices down the hall.

I remember the hole I made in the floorboards when I used

a hammer to smash that topaz into glittering shards, not

knowing it had a hardness of 8 on the Moh’s scale.

One Magoos night, when I worked the dinner shift, some guy I

didn’t know, looked all intense, right into in my eyes, and he said,

in all earnestness: “I saw you last night at the mile high church”.

And I didn’t know why. I walked away puzzled but kind of

stunned, some nerve struck like a tuning fork. I wondered

if maybe I dreamt him sitting there, saying such a strange thing.

Perhaps, that was the church I went to each night.

That was Magoos in the 1970’s on 6th Ave and Walker,

down Tribeca way. I worked making art and made life

my subject; danced to Television, Patty Smith and more;

gone now the Ocean Club, Tier 3, the Mudd Club, the art bands,

the New Wave, the No Wave, the Punk Rock and all those regulars.

At some point, memory fails me, I left Magoos (my shifts there ended),

for jazz up to Sheridan Square working for the mafia and

the hippie owners at The Sweet Basil Restaurant, now and

then gone too. Or perhaps it’s the other way around.

A waitress story for another day.

I was young and in love with a city broke and dirty,

rent I could afford and flirting flirty; madly inspired

with my ponytail swinging serving up chili, burgers

and ratatouille.

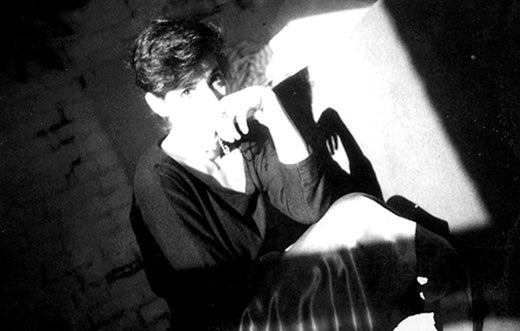

photo credits polaroids from John Street, Manhattan, by Aline Mare